Does Vitamin D Deficiency Cause Tinnitus

Disorder resulting from low blood levels of vitamin B12

Medical condition

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypocobalaminemia, cobalamin deficiency |

| |

| Cyanocobalamin | |

| Specialty | Neurology, hematology |

| Symptoms | Presence of anemia, decreased ability to think, depression, irritability, abnormal sensations, changes in reflexes[1] |

| Complications | Megaloblastic anemia[2] |

| Causes | Poor absorption, decreased intake, increased requirements[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood levels below 130–180 pmol/L (180–250 pg/mL) in adults[2] |

| Prevention | Supplementation in those at high risk[2] |

| Treatment | Supplementation by mouth or injection[3] |

| Frequency | 6% (< 60 years old), 20% (> 60 years old)[1] |

Vitamin B12 deficiency or Vitamin B12 deficiency anemia,[a] also known as cobalamin deficiency, is the medical condition of low blood and tissue levels of vitamin B12.[5] Symptoms may develop slowly and worsen over time. In mild deficiency, a person may feel tired and have a reduced number of red blood cells (anemia).[1] [6] In cases that often considered as moderate deficiency, soreness of the tongue, apthous ulcers, breathlessness, feeling like one is going to pass out, palpitations (rapid heartbeat), low blood pressure, jaundice, hair loss and severe joint pain (arthralgia) and the beginning of neurological symptoms, including abnormal sensations such as pins and needles, numbness and tinnitus may occur.[1] Severe deficiency may include symptoms of reduced heart function as well as more severe neurological symptoms, including changes in reflexes, poor muscle function, memory problems, blurred vision, irritability, ataxia, decreased taste, decreased level of consciousness, depression, anxiety, guilt and psychosis.[1] Infertility may occur.[1] [7] In young children, symptoms include poor growth, poor development, and difficulties with movement.[2] Without early treatment, some of the changes may be permanent.[8]

Causes are categorized as decreased absorption of vitamin B12 from the stomach or intestines, deficient intake, or increased requirements.[1] Decreased absorption may be due to atrophic gastritis, pernicious anemia, surgical removal of the stomach, chronic inflammation of the pancreas, intestinal parasites, certain medications, and some genetic disorders.[1] Medications that may decrease absorption include proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor blockers, and metformin.[9] Decreased intake may occur in vegetarians, vegans and the malnourished.[1] [10] Increased requirements occur in people with HIV/AIDS, and in those with shortened red blood cell lifespan.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on blood levels of vitamin B12 below 130–180 pmol/L (180 to 250 pg/mL) in adults.[2] Elevated methylmalonic acid levels may also indicate a deficiency.[2] A type of anemia known as megaloblastic anemia is often but not always present.[2] Individuals with low or "marginal" vitamin B12 in the range of 148–221 pmol/L (200–300 pg/mL) may not have classic neurological or hematological signs or symptoms.[2]

Treatment consists of oral or injected vitamin B12 supplementation; initially in high daily doses, followed by less frequent lower doses as the condition improves.[3] If a reversible cause is found, that cause should be corrected if possible.[11] If no reversible cause is found, or when found it cannot be eliminated, lifelong vitamin B12 administration is usually recommended.[12] Vitamin B12 deficiency is preventable with supplements containing the vitamin which is recommended in pregnant vegetarians and vegans, and not harmful in others.[2] Risk of toxicity due to vitamin B12 is low.[2]

Vitamin B12 deficiency in the US and the UK is estimated to occur in about 6 percent of those under the age of 60, and 20 percent of those over the age of 60.[1] In Latin America, about 40 percent are estimated to be affected, and this may be as high as 80 percent in parts of Africa and Asia.[1] Marginal deficiency is much more common and may occur in up to 40% of Western populations.[2]

Signs, symptoms and effects [edit]

The symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency can develop slowly and worsen over time - because is stored in substantial amounts in the liver mainly for about 3 to 5 years - until it is needed by the body. because may become used to not feeling well; therefore the symptoms may often goes unrecognized.[13] A mild deficiency may not cause any discernible symptoms. The signs are often digestive and neurological problems caused by a presence of anemia,[14] [15] [16] symptoms usually take time to appear before causes a pernicious anemia type.[13]

The deficiency often appears due to poor absorption or genetic disorders, which are rare to occur with decreased intake;[17] as anemia become more noticeable, symptoms may include feeling tiredness and weakness, dizziness, feeling faint (lightheadedness), headaches, a sore red tongue (glossitis), rapid heartbeat, breathlessness (rapid), pallor, low-grade fevers, shakiness and feeling constantly cold, cold hands and feet, low blood pressure (hypotension), stomach upset (dyspepsia), nausea, loss of appetite, weight loss and constipation or diarrhea.[13] [15] [16] [18] a wide symptoms may appear; such as angular cheilitis, mouth ulcers, bleeding gums, easy bruising and bleeding, tinnitus, hair loss and weakness, premature greying, a look of exhaustion and dark circles around the eyes, as well as brittle nails.[6]

Pallor, one of the signs of vitamin B12 deficiency

Severe deficiency symptoms [edit]

left untreated or in prolonged cases of vitamin B12 deficiency, it may damage nerve cells. If this happens, it may results:[17] [13]

- Abnormal sensations including tingling or numbness to the fingers and toes (pins and needles), sense loss and difficulty in proprioception (because affects the nervous system and brain)[19] [13]

- mental problems, including personality changes, depression,[15] Irritability,[16] confusion, decrease level of consciousness, brain fog (difficulty concentrating and sluggish responses)

- changes in mobility; including difficulty walking (ataxia), poor balance[16] and loss of sensation in the feet

- memory problems[15]

- blurred vision (disturbed)[18]

- muscle weakness, severe joint pain (arthralgia)[16]

In severe cases, it may including, mood swings, anxiety, dysuria (poor urine), fertility problems,[13] psychosis, cognitive impairment and changes in reflexes. If the deficiency is not corrected, deficiency may lead to more severe neurological complications; It may also produce a reduced sense of taste or smell.[20] and, in severe cases, dementia. Tissue deficiency resulting in negative effects in nerve cells, bone marrow, and the skin.[5]

The main type of vitamin B 12 deficiency anemia is pernicious anemia. It is characterized by a triad of symptoms:

- Anemia with bone marrow promegaloblastosis (megaloblastic anemia). This is due to the inhibition of DNA synthesis (specifically purines and thymidine).

- Gastrointestinal symptoms: alteration in bowel motility, such as mild diarrhea or constipation, and loss of bladder or bowel control.[21] These are thought to be due to defective DNA synthesis inhibiting replication in a site with a high turnover of cells. This may also be due to the autoimmune attack on the parietal cells of the stomach in pernicious anemia. There is an association with GAVE syndrome (commonly called watermelon stomach) and pernicious anemia.[22]

- Neurological symptoms: Sensory or motor deficiencies (absent reflexes, diminished vibration or soft touch sensation), subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord, or seizures.[23] [24] Deficiency symptoms in children include developmental delay, regression, irritability, involuntary movements and hypotonia.[25]

The presence of peripheral sensory-motor symptoms or subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord strongly suggests the presence of a B12 deficiency instead of folate deficiency. Methylmalonic acid, if not properly handled by B12, remains in the myelin sheath, causing fragility. Dementia and depression have been associated with this deficiency as well, possibly from the under-production of methionine because of the inability to convert homocysteine into this product. Methionine is a necessary cofactor in the production of several neurotransmitters.

Each of those symptoms can occur either alone or along with others. The neurological complex, defined as myelosis funicularis, consists of the following symptoms:

- Impaired perception of deep touch, pressure and vibration, loss of sense of touch, very annoying and persistent paresthesias

- Ataxia of dorsal column type

- Decrease or loss of deep muscle-tendon reflexes

- Pathological reflexes – Babinski, Rossolimo and others, also severe paresis

Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause severe and irreversible damage, especially to the brain and nervous system. These symptoms of neuronal damage may not reverse after correction of blood abnormalities, and the chance of complete reversal decreases with the length of time the neurological symptoms have been present. Elderly people are at an even higher risk of this type of damage.[26] In babies a number of neurological symptoms can be evident due to malnutrition or pernicious anemia in the mother. These include poor growth, apathy, having no desire for food, and developmental regression. While most symptoms resolve with supplementation some developmental and cognitive problems may persist.[27] [28]

Vitamin B12 deficiency may accompany certain eating disorders or restrictive diets.[29]

Only a small subset of dementia cases have been found to be reversible with vitamin B12 therapy.[30] Tinnitus may be associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.[31]

Effect of folic acid [edit]

Large amounts of folic acid can correct the megaloblastic anemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency without correcting the neurological abnormalities, and could also worsen the anemia and the cognitive symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.[2] Due to the fact that in the United States legislation has required enriched flour to contain folic acid to reduce cases of fetal neural-tube defects, consumers may be ingesting more folate than they realize.[32] To avoid this potential problem, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends that folic acid intake from fortified food and supplements should not exceed 1,000 μg daily in healthy adults.[2] [33] The European Food Safety Authority reviewed the safety question and agreed with the US that the tolerable upper intake levels (UL) be set at 1,000 μg.[34] The Japan National Institute of Health and Nutrition set the adult UL at 1,300 or 1,400 μg depending on age.[35]

Metabolic risk in offspring [edit]

Vitamin B12 is a critical micronutrient essential for supporting the increasing metabolic demands of the foetus during pregnancy.[36] B12 deficiency in pregnant women is increasingly common[37] and has been shown to be associated with major maternal health implications, including increased obesity,[37] higher body mass index (BMI),[38] insulin resistance,[36] gestational diabetes, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in later life.[39] A study in a pregnant white non-diabetic population in England, found that for every 1% increase in BMI, there was 0.6% decrease in circulating B12.[36] Furthermore, an animal study in ewes demonstrated that a B12, folate and methionine restricted diet around conception, resulted in offspring with higher adiposity, blood pressure and insulin resistance which could be accounted for altered DNA methylation patterns.[40]

Both vitamin B12 and folate are involved in the one-carbon metabolism cycle. In this cycle, vitamin B12 is a necessary cofactor for methionine synthase, an enzyme involved in the methylation of homocysteine to methionine.[41] DNA methylation is involved in the functioning of genes and is an essential epigenetic control mechanism in mammals. This methylation is dependent on methyl donors such as vitamin B12 from the diet.[42] Vitamin B12 deficiency has the potential to influence methylation patterns in DNA, besides other epigenetic modulators such as micro (RNAs), leading to the altered expression of genes.[43] [44] Consequently, an altered gene expression can possibly mediate impaired foetal growth and the programming of non-communicable diseases.[45] [43]

Vitamin B12 and folate status during pregnancy is associated with the increasing risk of low birth weight,[37] [46] preterm birth,[46] insulin resistance and obesity[36] [38] in the offspring. In addition it has been associated with adverse foetal and neonatal outcomes including neural tube defects (NTDs)[47] [48] [49] [50] and delayed myelination or demyelination.[51] [52] The mother's B12 status can be important in determining the later health of the child, as shown in the Pune maternal Nutrition Study, conducted in India. In this study mothers with high folate concentrations and low vitamin B12 concentrations, led to babies having a higher adiposity and insulin resistance at age 6. In the same study, over 60% of pregnant women were deficient in vitamin B12 and this was considered to increase the risk of gestational and later diabetes in the mothers.[38] Increased longitudinal cohort studies or randomised controlled trials are required to understand the mechanisms between vitamin B12 and metabolic outcomes, and to potentially offer interventions to improve maternal and offspring health.[53]

Cardiometabolic disease outcomes [edit]

Multiple studies have explored the association between vitamin B12 and metabolic disease outcomes, such as obesity, insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease.[54] [55] [56] A long-term study where vitamin B12 was supplemented across a period of 10 years, led to lower levels of weight gain in overweight or obese individuals (p < 0.05).[57]

There are several mechanisms which may explain the relationship between obesity and decreased vitamin B12 status. Vitamin B12 is a major dietary methyl donor, involved in the one-carbon cycle of metabolism and a recent genome-wide association (GWA) analysis showed that increased DNA methylation is associated with increased BMI in adults,[58] consequently a deficiency of vitamin B12 may disrupt DNA methylation and increase non- communicable disease risk. Vitamin B12 is also a co-enzyme which converts methylmalonyl- CoA to succinyl-CoA in the one carbon cycle. If this reaction cannot occur, methylmalonyl- CoA levels elevate, inhibiting the rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid oxidation (CPT1 – carnitine palmitoyl transferase), leading to lipogenesis and insulin resistance.[59] Further to this, reduced vitamin B12 concentrations in the obese population is thought to result from repetitive short-term restrictive diets and increased vitamin B12 requirements secondary to increased growth and body surface area.[54] [60] It has also been hypothesised that low vitamin B12 concentrations in obese individuals are a result of wrong feeding habits, where individuals consume a diet low in micronutrient density.[61] Finally, vitamin B12 is involved in the production of red blood cells, and vitamin B12 deficiency can result in anemia, which causes fatigue and the lack of motivation to exercise.[57] The investigation into the relationship between cardiovascular disease (CVD) and vitamin B12 has been limited, and there is still controversy as to whether primary intervention with vitamin B12 will lower cardiovascular disease.[62] Deficiency of vitamin B12 can impair the remethylation of homocysteine in the methionine cycle, and result in raised homocysteine levels.[63] There is much evidence linking elevated homocysteine concentrations with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease,[64] and homocysteine lowering treatments have led to improvements in cardiovascular reactivity and coagulation factors.[65] In adults with metabolic syndrome, individuals with low levels of vitamin B12 had higher levels of homocysteine compared to healthy subjects.[66] It is thus possible that vitamin B12 deficiency enhances the risk of developing cardiovascular disease in individuals who are obese.[54] Alternatively, low levels of vitamin B12 may increase the levels of proinflammatory proteins which may induce ischaemic stroke.[67] [68]

It is important to screen vitamin B12 deficiency in obese individuals, due to its importance in energy metabolism, and relationship with homocysteine and its potential to modulate weight gain.[61] More studies are needed to test for the causality of vitamin B12 and obesity using genetic markers.[69] A few studies have also reported no deficiency of vitamin B12 in obese individuals.[70] [71] [72] [73] Finally, a recent literature review conducted over 19 studies, found no evidence of an inverse association between BMI and circulating vitamin B12.[69]

Previous clinical and population-based studies have indicated that vitamin B12 deficiency is prevalent amongst adults with type 2 diabetes.[74] [75] Kaya et al., conducted a study in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, and found that obese women with insulin resistance had lower vitamin B12 concentrations compared to those without insulin resistance.[76] Similarly, in a study conducted in European adolescents, there was an association between high adiposity and higher insulin sensitivity with vitamin B12 concentrations. Individuals with a higher fat mass index and higher insulin sensitivity (high Homeostatic Model Assessment [HOMA] index) had lower plasma vitamin B12 concentrations.[77] Furthermore, a recent study conducted in India reported that mean levels of vitamin B12 decreased with increasing levels of glucose tolerance e.g. individuals with type 2 diabetes had the lowest values of vitamin B12, followed by individuals with pre-diabetes and normal glucose tolerance, respectively.[78] However, B12 levels of middle aged-women with and without metabolic syndrome[79] showed no difference in vitamin B12 levels between those with insulin resistance (IR) and those without. It is believed that malabsorption of vitamin B12 in diabetic patients, is due to individuals taking metformin therapy (an insulin sensitizer used for treating type 2 diabetes).[80] Furthermore, obese individuals with type 2 diabetes are likely to suffer from gastroesophageal reflux disease,[81] and take proton pump inhibitors, which further increased the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency.[69]

A recent literature review conducted over seven studies, found that there was limited evidence to show that low vitamin B12 status increased the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.[82] However, the review did not identify any associations between vitamin B12 and cardiovascular disease in the remaining four studies.[82] Currently, no data supports vitamin B12 supplementation on reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease. In a dose-response meta-analysis of five prospective cohort studies, it was reported that the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) did not change substantially with increasing dietary vitamin B12 intake.[83] Of these five studies, three of the studies stated a non-significant positive association and two of the studies demonstrated an inverse association between vitamin B12 supplementation and coronary heart disease (only one of the studies was significant).[83]

Neural tube defects (NTDs) [edit]

Neural tube defects (NTDs), including spina bifida, encephalocele and anencephaly, are debilitating birth defects which result from the failure of neural fold closure during embryonic development. The causes of NTDs are multifactorial, including folate deficiency, genetic and environment factors.[84] The WHO Technical Consultation has concluded that there is moderate evidence for the association between low vitamin B12 status and the increased risk of developing NTDs.[85] Given that vitamin B12 is a co-factor for methionine synthase within the folate cycle. If vitamin B12 supplies are depleted, folate becomes trapped and DNA synthesis and methylation reactions are impaired. DNA synthesis is critical for embryonic development. Further to this, cell-signalling events which control gene-expression are controlled by methylation reactions. As a result, adequate folate and vitamin B12 is needed to help prevent NTDs.[47]

Many studies have shown associations between maternal vitamin B12 status and NTD affected pregnancy.[47] [48] [49] [50] Low vitamin B12 concentrations have also been found in the amniotic fluid of NTD affected pregnancy.[86] [87] Additionally, a population-based case-control study (89 women with an NTD and 422 unaffected pregnant controls) in Canada conducted after the fortification of folic acid in flour, found almost a tripling in the risk of NTD, in the presence of low maternal vitamin B12 status (indicated by holoTC).[48]

Anemia [edit]

Vitamin B12 deficiency is one of the main causes of aneamia.[15] In countries where vitamin B12 deficiency is common, it is generally assumed that there is a greater risk of developing anemia. However, the overall contribution of vitamin B12 deficiency to the global incidence of anemia may not be significant, except in elderly individuals, vegetarians, cases of malabsorption and genetic disorders.[88] Vitamin B12 deficiency is also a major factor leading to megaloblastic anemia (or pernicious anemia);[7] a condition in which the body doesn't have enough healthy red blood cells, so tissues and organs don't get enough oxygen, causing feelings of weakness and tiredness, breathlessness, headaches, looking pale, feeling faint, rapid heartbeat, and dizziness.[15] [17] There are relatively few studies which have assessed the impact of haematological measures in response to vitamin B12 supplementation. One study in 184 premature infants, reported that individuals given monthly vitamin B12 injections (100 µg) or taking supplements of vitamin B12 and folic acid (100 µg/day), had higher haemoglobin concentrations after 10–12 weeks, compared to those only taking folic acid or those taking no vitamin B12 injections.[89] In deficient Mexican adult women and pre-schoolers, it was found that vitamin B12 supplementation did not affect any haematologic parameters.[90] [91]

Ageing [edit]

Vitamin B12 has been associated with disability in the elderly including the development of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and the risk of frailty.[92] Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of severe, irreversible vision loss in older adults.[93] During the advanced stages of age-related macular degeneration, individuals are impaired of carrying out basic activities such as driving, recognising faces and reading.[94] Several risk factors have been linked to age-related macular degeneration, including increasing age, family history, genetics, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, sunlight exposure and lifestyle (smoking and diet).[95] [96] A few cross-sectional studies have found associations between low vitamin B12 status and age-related macular degeneration cases.[96] [97] It has been shown that daily supplementation of vitamin B12, B6 and folate over a period of seven years can reduce the risk of age-related macular degeneration by 34% in women with increased risk of vascular disease (n=5,204).[98] However, another study failed to find an association between age-related macular degeneration and vitamin B12 status in a sample of 3,828 individuals representative of the non-institutionalized US population.[99]

Frailty is a geriatric condition which is characterized by diminished endurance, strength, and reduced physiological function that increases an individual's risk of mortality and impairs an individual from fulfilling an independent lifestyle.[100] Frailty is associated with an increased vulnerability to fractures, falls from heights, reduced cognitive function and more frequent hospitalisation.[101] The worldwide prevalence of frailty within the geriatric population is 13.9%,[102] therefore there is an urgent need to eliminate any risk factors associated with frailty. Poor vitamin B status has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of frailty. Two cross sectional studies have reported that deficiencies of vitamin B12 were associated with the length of hospital stay, as observed by serum vitamin B12 concentrations and methylmalonic acid (MMA) concentrations [139, 140].[103] [104] Furthermore, another study looking at elderly women (n=326), found that certain genetic variants associated with vitamin B12 status (Transcobalamin 2) may contribute to reduced energy metabolism, consequently contributing to frailty.[105] In contrast, a recent study by Dokuzlar et al., found that there was no association between vitamin B12 levels and frailty in the geriatric population (n=335).[106] Given that there are limited studies, which have assessed the relationship between vitamin B12 and frailty status, more longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the relationship.

Neurological decline [edit]

Severe vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, which involves demyelination of the posterior and lateral columns of the spinal cord.[107] Symptoms include memory and cognitive impairment, sensory loss, motor disturbances, loss of posterior column functions and disturbances in proprioception.[108] [109] In advanced stages of vitamin B12 deficiency, cases of psychosis, paranoia and severe depression have been observed, which may lead to permanent disability if left untreated.[107] [108] [109] Studies have shown the rapid reversal of the neurological symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, after treatment with high-dose of vitamin B12 supplementation; suggesting the importance of prompt treatment in reversing neurological manifestations.[110]

Cognitive decline [edit]

Elderly individuals are currently assessed on vitamin B12 status during the screening process for dementia. Studies investigating the association between vitamin B12 concentrations and cognitive status have produced inconclusive results.[92] [111] [112] It has been shown that elevated MMA concentrations are associated with decreased cognitive decline and Alzheimer's Disease.[113] In addition, low vitamin B12 and folate intakes have shown associations with hyperhomocysteinemia, which is associated with cerebrovascular disease, cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia in prospective studies.[114]

There are limited intervention studies which have investigated the effect of supplementation of vitamin B12 and cognitive function. A Cochrane review, analysing two studies, found no effect of vitamin B12 supplementation on the cognitive scores of older adults.[115] A recent longitudinal study in elderly individuals, found that individuals had a higher risk of brain volume loss over a 5-year period, if they had lower vitamin B12 and holoTC levels and higher plasma tHcy and MMA levels.[116] More intervention studies are needed to determine the modifiable effects of vitamin B12 supplementation on cognition.[92]

Osteoporosis [edit]

There has been growing interest on the effect of low serum vitamin B12 concentrations on bone health.[117] [118] Recent studies have found a connection between elevated plasma tHcy and an increased risk of bone fractures, but is unknown whether this is related to the increased levels of tHcy or to vitamin B12 levels (which are involved in homocysteine metabolism).[119] Results from the third NHANES conducted in the United States, found that individuals had significantly lower bone mass density (BMD) and higher osteoporosis rates with each higher quartile of serum MMA (n= 737 men and 813 women).[120] Given that poor bone mineralization has been found in individuals with pernicious anemia,[121] and that the content of vitamin B12 within bone cells in culture has shown to affect the functioning of bone forming cells (osteoblasts);[122] it is possible that vitamin B12 deficiency is causally related to poor bone health.

Randomized intervention trials investigating the association of vitamin B12 supplementation and bone health have yielded mixed results. Two studies conducted in osteoporotic risk patients with hyperhomocysteinemia and individuals who had undergone a stroke, found positive effects between supplementation of B vitamins on BMD.[123] [124] However, no improvement in BMD was observed in a group of healthy older people.[125] Further, controlled trials are needed to confirm the impact and mechanisms vitamin B12 deficiency has on bone mineralization.[85]

Causes [edit]

Impaired absorption [edit]

- Inadequate absorption is the most common cause of Vitamin B12 Deficiency.[126] [127] Selective impaired absorption of vitamin B12 due to intrinsic factor deficiency. This may be caused by the loss of gastric parietal cells in chronic atrophic gastritis (in which case, the resulting megaloblastic anemia takes the name of "pernicious anemia"), or may result from wide surgical resection of stomach (for any reason), or from rare hereditary causes of impaired synthesis of intrinsic factor. B12 deficiency is more common in the elderly because gastric intrinsic factor, necessary for absorption of the vitamin, is deficient, due to atrophic gastritis.[128]

- Impaired absorption of vitamin B12 in the setting of a more generalized malabsorption or maldigestion syndrome. This includes any form due to structural damage or wide surgical resection of the terminal ileum (the principal site of vitamin B12 absorption).

- Forms of achlorhydria (including that artificially induced by drugs such as proton pump inhibitors and histamine 2 receptor antagonists) can cause B12 malabsorption from foods, since acid is needed to split B12 from food proteins and salivary binding proteins.[129] This process is thought to be the most common cause of low B12 in the elderly, who often have some degree of achlorhydria without being formally low in intrinsic factor. This process does not affect absorption of small amounts of B12 in supplements such as multivitamins, since it is not bound to proteins, as is the B12 in foods.[128]

- Surgical removal of the small bowel (for example in Crohn's disease) such that the patient presents with short bowel syndrome and is unable to absorb vitamin B12. This can be treated with regular injections of vitamin B12.

- Long-term use of ranitidine hydrochloride may contribute to deficiency of vitamin B12.[130]

- Untreated celiac disease may also cause impaired absorption of this vitamin, probably due to damage to the small bowel mucosa. In some people, vitamin B12 deficiency may persist despite treatment with a gluten-free diet and require supplementation.[131]

- Some bariatric surgical procedures, especially those that involve removal of part of the stomach, such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. (Procedures such as the adjustable gastric band type do not appear to affect B12 metabolism significantly).[ citation needed ]

- Bacterial overgrowth within portions of the small intestine, such as may occur in blind loop syndrome, (a condition due to a loop forming in the intestine) may result in increased consumption of intestinal vitamin B12 by these bacteria.[132]

- The diabetes medication metformin may interfere with B12 dietary absorption.[133]

- A genetic disorder, transcobalamin II deficiency can be a cause.[134]

- Nitrous oxide exposure, and recreational use.[135] [134]

- Infection with the Diphyllobothrium latum tapeworm

- Chronic exposure to toxigenic molds and mycotoxins found in water damaged buildings.[136] [137]

- B12 deficiency caused by Helicobacter pylori was positively correlated with CagA positivity and gastric inflammatory activity, rather than gastric atrophy.[138]

Inadequate intake [edit]

Inadequate dietary intake of animal products such as eggs, meat, milk, fish, fowl (and some type of edible algae) can result in a deficiency state.[139] Vegans, and to a lesser degree vegetarians, are at risk for B12 deficiency if they do not consume either a dietary supplement or vitamin-fortified foods. Children are at a higher risk for B12 deficiency due to inadequate dietary intake, as they have fewer vitamin stores and a relatively larger vitamin need per calorie of food intake.[140]

Increased need [edit]

Increased needs by the body can occur due to AIDS and hemolysis (the breakdown of red blood cells), which stimulates increased red cell production.[1]

Mechanism [edit]

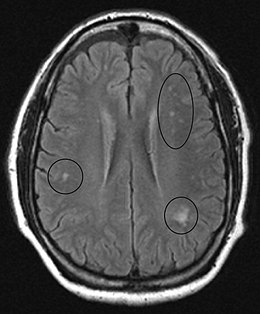

MRI image of the brain in vitamin B12 deficiency, axial view showing the "precontrast FLAIR image": note the abnormal lesions (circled) in the periventricular area suggesting white matter pathology.

MRI image of the cervical spinal cord in vitamin B12 deficiency showing subacute combined degeneration. (A) The midsagittal T2 weighted image shows linear hyperintensity in the posterior portion of the cervical tract of the spinal cord (black arrows). (B) Axial T2 weighted images reveal the selective involvement of the posterior columns.

Physiology [edit]

The total amount of vitamin B12 stored in the body is between two and five milligrams in adults. Approximately 50% is stored in the liver, but approximately 0.1% is lost each day, due to secretions into the gut—not all of the vitamin in the gut is reabsorbed. While bile is the main vehicle for B12 excretion, most of this is recycled via enterohepatic circulation. Due to the extreme efficiency of this mechanism, the liver can store three to five years worth of vitamin B12 under normal conditions and functioning.[141] However, the rate at which B12 levels may change when dietary intake is low depends on the balance between several variables.[142]

Pathophysiology [edit]

Vitamin B12 deficiency causes particular changes to the metabolism of two clinically relevant substances in humans:

- Homocysteine (homocysteine to methionine, catalysed by methionine synthase) leading to hyperhomocysteinemia

- Methylmalonic acid (methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, of which methylmalonyl-CoA is made from methylmalonic acid in a preceding reaction)

Methionine is activated to S-adenosyl methionine, which aids in purine and thymidine synthesis, myelin production, protein/neurotransmitters/fatty acid/phospholipid production and DNA methylation. 5-Methyl tetrahydrofolate provides a methyl group, which is released to the reaction with homocysteine, resulting in methionine. This reaction requires cobalamin as a cofactor. The creation of 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate is an irreversible reaction. If B12 is absent, the forward reaction of homocysteine to methionine does not occur, homocysteine concentrations increase, and the replenishment of tetrahydrofolate stops.[143] Because B12 and folate are involved in the metabolism of homocysteine, hyperhomocysteinuria is a non-specific marker of deficiency. Methylmalonic acid is used as a more specific test of B12 deficiency.

Nervous system [edit]

Early changes include a spongiform state of neural tissue, along with edema of fibers and deficiency of tissue. The myelin decays, along with axial fiber. In later phases, fibric sclerosis of nervous tissues occurs. Those changes occur in dorsal parts of the spinal cord and to pyramidal tracts in lateral cords and are called subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord.[144] Pathological changes can be noticed as well in the posterior roots of the cord and, to lesser extent, in peripheral nerves.

In the brain itself, changes are less severe: They occur as small sources of nervous fibers decay and accumulation of astrocytes, usually subcortically located, and also round hemorrhages with a torus of glial cells.

MRI of the brain may show periventricular white matter abnormalities. MRI of the spinal cord may show linear hyperintensity in the posterior portion of the cervical tract of the spinal cord, with selective involvement of the posterior columns.

Diagnosis [edit]

There is no golden standard assay to confirm a vitamin B12 deficiency.[145] Serum levels of B12 are often low in vitamin B12 deficiency, but if there are clinical signs that conflict with normal levels of vitamin B12; additional investigations are justified. Diagnosis is often suspected first, as diagnosis usually requires several tests, these include:[146] [147] [148]

- Complete blood count; a routine complete blood count shows anemia with an elevated mean corpuscular volume (MCV)[147] [148]

- Serium vitamin B12; a level below normal indicates a deficiency[145] [146] [147]

- Methylmalonic acid and/or homocysteine; If the serum vitamin B12 is at the normal level, methylmalonic acid and/or homocysteine assay is required. higher levels indicate a deficency, indicators are usually more reliable[149] [150] [151]

- Intrinsic factor and parietal cell antibodies; The blood is tested for antibodies against intrinsic factor and the parietal cells of the stomach[146] [148]

In some cases, a peripheral blood smear may be used; which may allow to show macrocytes and hypersegmented polymorphonuclear leukocytes.[148] [152]

If nervous system damage is present and blood testing is inconclusive, a lumbar puncture to measure cerebrospinal fluid B-12 levels may be done.[153] On bone marrow aspiration or biopsy, megaloblasts are seen.[154]

The Schilling test was a radio-isotope method, now outdated, of testing for low vitamin B12.[148] [155]

Serum Levels [edit]

A blood test will provide the levels of vitamin B12, Vitamin B12 deficiency can be determined by serum.[147] In recent years, vitamin B12 serum has been considered somewhat unreliable,[156] as deficiency may be present within the normal serum levels.[156] When clinical symptoms conflict with the serum normal levels, other tests may be required. The normal serum levels are considered to be between (200–980 pg/mL). A levels less than 350 pg/mL are considered a borderline deficiency; and a levels less than 200 pg/mL are considered a deficiency; while a levels below 170 pg/mL are considered severe.[145]

Some researchers have suggested that current standards for vitamin B12 levels are too low.[157] a japanese study showed that the normal limits should be between (500-1300 pg/ml).[158]

Treatment [edit]

Hydroxocobalamin injection is a clear red liquid solution.

B12 can be supplemented orally or by injection and appears to be equally effective in those with low levels due to deficient absorption of B12. When large doses are given by mouth, B12 absorption does not rely on the presence of intrinsic factor or an intact ileum. Instead, these large-dose supplements result in 1% to 5% absorption along the entire intestine by passive diffusion. Generally 1 to 2 mg daily is required as a large dose. Even pernicious anemia can be treated entirely by the oral route.[3] [159] [160]

Epidemiology [edit]

Vitamin B12 deficiency is common and occurs worldwide. In the US and UK, around 6 percent of the general population have the deficiency; in those over the age of sixty, around 20 percent are deficient. In under-developed countries, the rates are even higher: across Latin America 40 percent are deficient; in some parts of Africa, 70 percent; and in some parts of India, 70 to 80 percent.[1]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vitamin B12 deficiency may be considered a global public health problem affecting millions of individuals.[161] However, the incidence and prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency worldwide is unknown due to the limited population-based data available (see table below).

Developed countries such as the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom have relatively constant mean vitamin B12 concentrations.[162] The data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) reported the prevalence of serum vitamin B12 concentrations in the United States population between 1999 to 2002.[163] [164] Serum vitamin B12 concentrations of < 148 pmol/L was present in < 1% of children and adolescents. In adults aged 20–39 years, concentrations were below this cut-off in ≤ 3% of individuals. In the elderly (70 years and older), ≈ 6% of persons had a vitamin B12 concentration below the cut-off.

Furthermore, ≈ 14-16% of adults and > 20% of elderly individuals showed evidence of marginal vitamin B12 depletion (serum vitamin B12: 148-221 pmol/L).[163] [164] In the United Kingdom, a National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) was conducted in adults aged between 19 to 64 years in 2000–2001[165] and in elderly individuals (≥ 65 years) in 1994–95.[166] Six percent of men (n = 632) and 10% of women (n = 667) had low serum vitamin B12 concentrations, defined as < 150 pmol/L. In a subgroup of women of reproductive age (19 to 49 years), 11% had low serum B12 concentrations < 150 pmol/L (n = 476). The prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency increased substantially in the elderly, where 31% of the elderly had vitamin B12 levels below 130 pmol/L. In the most recent NDNS survey conducted between 2008-2011, serum vitamin B12 was measured in 549 adults.[167] The mean serum vitamin B12 concentration for men (19–64 years) was 308 pmol/L, of which 0.9% of men had low serum B12 concentrations < 150 pmol/L. In women aged between 19–64 years, the mean serum vitamin B12 concentration was slightly lower than men (298 pmol/L), with 3.3% having low vitamin B12 concentrations < 150 pmol/L.[167] In Germany, a national survey in 1998 was conducted in 1,266 women of childbearing age. Approximately, 14.7% of these women had mean serum vitamin B12 concentrations of < 148 pmol/L.[168]

Few studies have reported vitamin B12 status on a national level in non-Western countries.[169] Of these reported studies, vitamin B12 deficiency was prevalent among school- aged children in Venezuela (11.4%),[170] children aged 1–6 years in Mexico (7.7%),[171] women of reproductive age in Vietnam (11.7%),[172] pregnant women in Venezuela (61.34%)[170] and in the elderly population (> 65 years) in New Zealand (12%).[173] Currently, there are no nationally representative surveys for any African or South Asian countries. However, the very few surveys which have investigated vitamin B12 deficiency in these countries have been based on local or district level data. These surveys have reported a high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency (< 150 pmol/L), among 36% of breastfed and 9% of non-breastfed children (n = 2482) in New Delhi[174] and 47% of adults (n = 204)[175] in Pune, Maharashtra, India. Furthermore, in Kenya a local district survey in Embu (n = 512) revealed that 40% of school-aged children in Kenya had vitamin B12 deficiency.[176]

Table showing worldwide prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency (serum/plasma B12 < 148 or 150 pmol/L)

| Group | Number of studies | Number of participants | Vitamin B12 deficiency (%) |

| Children (< 1y – 18 years) | 14 | 22,331 | 12.5 |

| Pregnant women | 11 | 11,381 | 27.5 |

| Non-pregnant women | 16 | 18,520 | 16 |

| All adults (Under 60 years) | 18 | 81.438 | 6 |

| Elderly (60+ years) | 25 | 30,449 | 19 |

Derived from Table 2 available on [177]

History [edit]

Between 1849 and 1887, Thomas Addison described a case of pernicious anemia, William Osler and William Gardner first described a case of neuropathy, Hayem described large red cells in the peripheral blood in this condition, which he called "giant blood corpuscles" (now called macrocytes), Paul Ehrlich identified megaloblasts in the bone marrow, and Ludwig Lichtheim described a case of myelopathy.[178] During the 1920s, George Whipple discovered that ingesting large amounts of liver seemed to most rapidly cure the anemia of blood loss in dogs, and hypothesized that eating liver might treat pernicious anemia.[179] Edwin Cohn prepared a liver extract that was 50 to 100 times more potent in treating pernicious anemia than the natural liver products. William Castle demonstrated that gastric juice contained an "intrinsic factor" which when combined with meat ingestion resulted in absorption of the vitamin in this condition.[178] In 1934, George Whipple shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with William P. Murphy and George Minot for discovery of an effective treatment for pernicious anemia using liver concentrate, later found to contain a large amount of vitamin B12.[178] [180]

Society and culture [edit]

In 2020, a case of Vitamin B12 deficiency made headlines when it emerged that a teenager from Bristol, England, had gone blind (via atrophy of the optic nerves) and sustained severe pernicious anemia after eating a highly restricted diet consisting of white bread, potato crisps and chips with virtually no meat.[181] The patient reported that they ate these types of food because they disliked the texture of other food, and thus ate their restricted diet obsessively.[182] [183] In this instance, the hypocobalaminemia was accompanied by other consequences of the malnutrition, including zinc and selenium deficiency, hypovitaminosis D, hypocupremia and reduced bone density.[184]

Other animals [edit]

Ruminants, such as cattle and sheep, absorb B12 synthesized by their gut bacteria.[185] Sufficient amounts of cobalt and copper need to be consumed for this B12 synthesis to occur.[186]

In the early 20th century, during the development for farming of the North Island Volcanic Plateau of New Zealand, cattle suffered from what was termed "bush sickness". It was discovered in 1934 that the volcanic soils lacked the cobalt salts essential for synthesis of vitamin B12 by their gut bacteria.[187] [186] The "coast disease" of sheep in the coastal sand dunes of South Australia in the 1930s was found to originate in nutritional deficiencies of the trace elements, cobalt and copper. The cobalt deficiency was overcome by the development of "cobalt bullets", dense pellets of cobalt oxide mixed with clay given orally, which then was retained in the animal's rumen.[186] [188]

Notes [edit]

- ^ In most common cases, a lack of vitamin B12 leads to anemia; is the general term for having either fewer red blood cells than normal or having an abnormally low amount of haemoglobin in each red blood cell - the hematology tests showed that only 20% of patients did not have anemia.[4]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S (September 2014). "Vitamin B12 deficiency" (PDF). BMJ. 349: g5226. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226. PMID 25189324. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Vitamin B12 – Health Professional Fact Sheet". National Institutes of Health: Office of Dietary Supplements. 2016-02-11. Archived from the original on 2016-07-27. Retrieved 2016-07-15 .

- ^ a b c Wang H, Li L, Qin LL, Song Y, Vidal-Alaball J, Liu TH (March 2018). "Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (3): CD004655. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004655.pub3. PMC5112015. PMID 29543316.

- ^ Lindenbaum, J.; Healton, E. B.; Savage, D. G.; Brust, J. C.; Garrett, T. J.; Podell, E. R.; Marcell, P. D.; Stabler, S. P.; Allen, R. H. (1988-06-30). "Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 318 (26): 1720–1728. doi:10.1056/NEJM198806303182604. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 3374544.

- ^ a b Herrmann W (2011). Vitamins in the prevention of human diseases. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 245. ISBN978-3110214482.

- ^ a b "Pernicious Anemia Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination". web.archive.org. 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2021-11-28 .

- ^ a b "Complications". nhs.uk. 2017-10-20.

- ^ Lachner C, Steinle NI, Regenold WT (2012). "The neuropsychiatry of vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly patients". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 24 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11020052. PMID 22450609.

- ^ Miller JW (July 2018). "Proton Pump Inhibitors, H2-Receptor Antagonists, Metformin, and Vitamin B-12 Deficiency: Clinical Implications". Advances in Nutrition. 9 (4): 511S–518S. doi:10.1093/advances/nmy023. PMC6054240. PMID 30032223.

- ^ Pawlak R, Parrott SJ, Raj S, Cullum-Dugan D, Lucus D (February 2013). "How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians?". Nutrition Reviews. 71 (2): 110–7. doi:10.1111/nure.12001. PMID 23356638.

- ^ Hankey GJ, Wardlaw JM (2008). Clinical neurology. London: Manson. p. 466. ISBN978-1840765182.

- ^ Schwartz W (2012). The 5-minute pediatric consult (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 535. ISBN9781451116564.

- ^ a b c d e f "21 Things You Should Know About Vitamin B12 Deficiency". Health.com . Retrieved 2021-10-13 .

- ^ Reynolds EH (2014). "The neurology of folic acid deficiency". In Biller J, Ferro JM (eds.). Neurologic aspects of systemic disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 120. pp. 927–43. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-4087-0.00061-9. ISBN9780702040870. PMID 24365361.

- ^ a b c d e f "Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment". 2021-07-28. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-09-13 .

- ^ a b c d e "Articles". Cedars-Sinai . Retrieved 2021-09-13 .

- ^ a b c "Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anemia | Michigan Medicine". www.uofmhealth.org . Retrieved 2021-10-08 .

- ^ a b "How a Vitamin B Deficiency Affects Blood Pressure". LIVESTRONG.COM . Retrieved 2021-09-13 .

- ^ "Complications". nhs.uk. 2017-10-20.

- ^ Team, Msensory. "Vitamin B12 deficiency symptoms: Loss of smell could be one of the signs | Express.co.uk – msensory". Retrieved 2021-09-30 .

- ^ Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Citton V, Manara R, Pompanin S, Binotto G, Adami F (November 2013). "Cobalamin deficiency: clinical picture and radiological findings". Nutrients. 5 (11): 4521–39. doi:10.3390/nu5114521. PMC3847746. PMID 24248213.

- ^ Amarapurka DN, Patel ND (September 2004). "Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) Syndrome" (PDF). Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 52: 757. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Matsumoto A, Shiga Y, Shimizu H, Kimura I, Hisanaga K (April 2009). "[Encephalomyelopathy due to vitamin B12 deficiency with seizures as a predominant symptom]". Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology. 49 (4): 179–85. doi:10.5692/clinicalneurol.49.179. PMID 19462816.

- ^ Kumar S (March 2004). "Recurrent seizures: an unusual manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency". Neurology India. 52 (1): 122–3. PMID 15069260. Archived from the original on 2011-01-23.

- ^ Kliegman RM, Stanton B, St Geme J, Schor NF, eds. (2016). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (20th ed.). pp. 2319–26. ISBN978-1-4557-7566-8.

- ^ Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J, Allen RH (October 1997). "Vitamin B-12 deficiency in the elderly: current dilemmas". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 66 (4): 741–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/66.4.741. PMID 9322547.

- ^ Dror DK, Allen LH (May 2008). "Effect of vitamin B12 deficiency on neurodevelopment in infants: current knowledge and possible mechanisms". Nutrition Reviews. 66 (5): 250–5. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00031.x. PMID 18454811.

- ^ Black MM (June 2008). "Effects of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency on brain development in children". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 29 (2 Suppl): S126-31. doi:10.1177/15648265080292S117. PMC3137939. PMID 18709887.

- ^ O'Gorman P, Holmes D, Ramanan AV, Bose-Haider B, Lewis MJ, Will A (June 2002). "Dietary vitamin B12 deficiency in an adolescent white boy". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 55 (6): 475–6. doi:10.1136/jcp.55.6.475. PMC1769668. PMID 12037034.

- ^ Moore E, Mander A, Ames D, Carne R, Sanders K, Watters D (April 2012). "Cognitive impairment and vitamin B12: a review". International Psychogeriatrics. 24 (4): 541–56. doi:10.1017/S1041610211002511. PMID 22221769. S2CID 206300763.

- ^ Zempleni J, Suttie JW, Gregory III JF, Stover PJ, eds. (2014). Handbook of vitamins (Fifth ed.). Hoboken: CRC Press. p. 477. ISBN9781466515574. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17.

- ^ Beck M (January 18, 2011). "Sluggish? Confused? Vitamin B12 May Be Low". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (1998). "Folate". Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 196–305. ISBN978-0-309-06554-2 . Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals" (PDF). European Food Safety Authority. 2006.

- ^ Shibata K, Fukuwatari T, Imai E, Hayakawa T, Watanabe F, Takimoto H, Watanabe T, Umegaki K (2013). "Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 2010: Water-Soluble Vitamins". Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. 2013 (59): S67–S82.

- ^ a b c d Knight, Bridget Ann; Shields, Beverley M.; Brook, Adam; Hill, Anita; Bhat, Dattatray S.; Hattersley, Andrew T.; Yajnik, Chittaranjan S. (2015-08-19). Sengupta, Shantanu (ed.). "Lower Circulating B12 Is Associated with Higher Obesity and Insulin Resistance during Pregnancy in a Non-Diabetic White British Population". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0135268. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035268K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135268. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC4545890. PMID 26288227.

- ^ a b c "Erratum for Sukumar N et al. Prevalence of vitamin B-12 insufficiency during pregnancy and its effect on offspring birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:1232–51". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 105 (1): 241.1–241. January 2017. doi:10.3945/ajcn.116.148585. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 28049667.

- ^ a b c Yajnik, C. S.; Deshpande, S. S.; Jackson, A. A.; Refsum, H.; Rao, S.; Fisher, D. J.; Bhat, D. S.; Naik, S. S.; Coyaji, K. J.; Joglekar, C. V.; Joshi, N. (2007-11-29). "Vitamin B12 and folate concentrations during pregnancy and insulin resistance in the offspring: the Pune Maternal Nutrition Study". Diabetologia. 51 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0793-y. ISSN 0012-186X. PMC2100429. PMID 17851649.

- ^ Krishnaveni, G. V.; Hill, J. C.; Veena, S. R.; Bhat, D. S.; Wills, A. K.; Karat, C. L. S.; Yajnik, C. S.; Fall, C. H. D. (November 2009). "Low plasma vitamin B12 in pregnancy is associated with gestational 'diabesity' and later diabetes". Diabetologia. 52 (11): 2350–2358. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1499-0. ISSN 0012-186X. PMC3541499. PMID 19707742.

- ^ Sinclair, K. D.; Allegrucci, C.; Singh, R.; Gardner, D. S.; Sebastian, S.; Bispham, J.; Thurston, A.; Huntley, J. F.; Rees, W. D.; Maloney, C. A.; Lea, R. G. (2007-12-04). "DNA methylation, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in offspring determined by maternal periconceptional B vitamin and methionine status". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (49): 19351–19356. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10419351S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707258104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC2148293. PMID 18042717.

- ^ Finer, S.; Saravanan, P.; Hitman, G.; Yajnik, C. (March 2014). "The role of the one-carbon cycle in the developmental origins of Type 2 diabetes and obesity". Diabetic Medicine. 31 (3): 263–272. doi:10.1111/dme.12390. PMID 24344881.

- ^ Krikke, Gg; Grooten, Ij; Vrijkotte, Tgm; van Eijsden, M; Roseboom, Tj; Painter, Rc (February 2016). "Vitamin B 12 and folate status in early pregnancy and cardiometabolic risk factors in the offspring at age 5-6 years: findings from the ABCD multi-ethnic birth cohort". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 123 (3): 384–392. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13574. PMID 26810674. S2CID 1822164.

- ^ a b Adaikalakoteswari, Antonysunil; Vatish, Manu; Alam, Mohammad Tauqeer; Ott, Sascha; Kumar, Sudhesh; Saravanan, Ponnusamy (2017-11-01). "Low Vitamin B12 in Pregnancy Is Associated With Adipose-Derived Circulating miRs Targeting PPARγ and Insulin Resistance". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 102 (11): 4200–4209. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01155. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 28938471.

- ^ Chango, Abalo; Pogribny, Igor (2015-04-14). "Considering Maternal Dietary Modulators for Epigenetic Regulation and Programming of the Fetal Epigenome". Nutrients. 7 (4): 2748–2770. doi:10.3390/nu7042748. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC4425171. PMID 25875118.

- ^ Yajnik, Chittaranjan Sakerlal; Deshmukh, Urmila Shailesh (June 2012). "Fetal programming: Maternal nutrition and role of one-carbon metabolism". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 13 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1007/s11154-012-9214-8. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 22415298. S2CID 11186195.

- ^ a b Rogne, Tormod; Tielemans, Myrte J.; Chong, Mary Foong-Fong; Yajnik, Chittaranjan S.; Krishnaveni, Ghattu V.; Poston, Lucilla; Jaddoe, Vincent W. V.; Steegers, Eric A. P.; Joshi, Suyog; Chong, Yap-Seng; Godfrey, Keith M. (2017-01-20). "Associations of Maternal Vitamin B12 Concentration in Pregnancy With the Risks of Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data". American Journal of Epidemiology. 185 (3): 212–223. doi:10.1093/aje/kww212. ISSN 0002-9262. PMC5390862. PMID 28108470.

- ^ a b c Molloy, A. M.; Kirke, P. N.; Troendle, J. F.; Burke, H.; Sutton, M.; Brody, L. C.; Scott, J. M.; Mills, J. L. (2009-03-01). "Maternal Vitamin B12 Status and Risk of Neural Tube Defects in a Population With High Neural Tube Defect Prevalence and No Folic Acid Fortification". Pediatrics. 123 (3): 917–923. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1173. hdl:2262/34511. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC4161975. PMID 19255021.

- ^ a b c Ray, Joel G.; Wyatt, Philip R.; Thompson, Miles D.; Vermeulen, Marian J.; Meier, Chris; Wong, Pui-Yuen; Farrell, Sandra A.; Cole, David E. C. (May 2007). "Vitamin B12 and the Risk of Neural Tube Defects in a Folic-Acid-Fortified Population". Epidemiology. 18 (3): 362–366. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000257063.77411.e9. ISSN 1044-3983. PMID 17474166. S2CID 21094981.

- ^ a b "Maternal plasma folate and vitamin B12 are independent risk factors for neural tube defects". QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. November 1993. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a068749. ISSN 1460-2393.

- ^ a b Gaber, K.R., et al., Maternal vitamin B12 and the risk of fetal neural tube defects in Egyptian patients. Clin Lab, 2007. 53(1-2): p. 69-75.

- ^ Black, Maureen M. (June 2008). "Effects of Vitamin B 12 and Folate Deficiency on Brain Development in Children". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 29 (2_suppl1): S126–S131. doi:10.1177/15648265080292S117. ISSN 0379-5721. PMC3137939. PMID 18709887.

- ^ Lövblad, Karl-Olof; Ramelli, Gianpaolo; Remonda, Luca; Nirkko, Arto C.; Ozdoba, Christoph; Schroth, Gerhard (February 1997). "Retardation of myelination due to dietary vitamin B12 deficiency: cranial MRI findings". Pediatric Radiology. 27 (2): 155–158. doi:10.1007/s002470050090. ISSN 0301-0449. PMID 9028851. S2CID 25039442.

- ^ Li, Zhen; Gueant-Rodriguez, Rosa-Maria; Quilliot, Didier; Sirveaux, Marie-Aude; Meyre, David; Gueant, Jean-Louis; Brunaud, Laurent (October 2018). "Folate and vitamin B12 status is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in morbid obesity". Clinical Nutrition. 37 (5): 1700–1706. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.07.008. PMID 28780990.

- ^ a b c Pinhas-Hamiel, Orit; Doron-Panush, Noa; Reichman, Brian; Nitzan-Kaluski, Dorit; Shalitin, Shlomit; Geva-Lerner, Liat (2006-09-01). "Obese Children and Adolescents: A Risk Group for Low Vitamin B 12 Concentration". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 160 (9): 933–936. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.9.933. ISSN 1072-4710. PMID 16953016.

- ^ MacFarlane, Amanda J; Greene-Finestone, Linda S; Shi, Yipu (2011-10-01). "Vitamin B-12 and homocysteine status in a folate-replete population: results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 94 (4): 1079–1087. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.020230. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 21900461.

- ^ Madan, Atul; Orth, Whitney; Tichansky, David; Ternovits, Craig (2006-05-01). "Vitamin and Trace Mineral Levels after Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass". Obesity Surgery. 16 (5): 603–606. doi:10.1381/096089206776945057. PMID 16687029. S2CID 31410788.

- ^ a b Nachtigal, M.C.; Patterson, Ruth E.; Stratton, Kayla L.; Adams, Lizbeth A.; Shattuck, Ann L.; White, Emily (October 2005). "Dietary Supplements and Weight Control in a Middle-Age Population". The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 11 (5): 909–915. doi:10.1089/acm.2005.11.909. ISSN 1075-5535. PMID 16296926.

- ^ Dick, Katherine J; Nelson, Christopher P; Tsaprouni, Loukia; Sandling, Johanna K; Aïssi, Dylan; Wahl, Simone; Meduri, Eshwar; Morange, Pierre-Emmanuel; Gagnon, France; Grallert, Harald; Waldenberger, Melanie (June 2014). "DNA methylation and body-mass index: a genome-wide analysis". The Lancet. 383 (9933): 1990–1998. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62674-4. PMID 24630777. S2CID 18026508.

- ^ Adaikalakoteswari, Antonysunil; Jayashri, Ramamurthy; Sukumar, Nithya; Venkataraman, Hema; Pradeepa, Rajendra; Gokulakrishnan, Kuppan; Anjana, Ranjit Mohan; McTernan, Philip G.; Tripathi, Gyanendra; Patel, Vinod; Kumar, Sudhesh (2014-09-26). "Vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with adverse lipid profile in Europeans and Indians with type 2 diabetes". Cardiovascular Diabetology. 13 (1): 129. doi:10.1186/s12933-014-0129-4. ISSN 1475-2840. PMC4189588. PMID 25283155.

- ^ Wall, С., Food and Nutrition Guidelines for Healthy Adolescents. Ministry of Health. Wellington, New Zealand, 1998.

- ^ a b Thomas-Valdés, Samanta; Tostes, Maria das Graças V.; Anunciação, Pamella C.; da Silva, Bárbara P.; Sant'Ana, Helena M. Pinheiro (2017-10-13). "Association between vitamin deficiency and metabolic disorders related to obesity". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 57 (15): 3332–3343. doi:10.1080/10408398.2015.1117413. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 26745150. S2CID 19077356.

- ^ Debreceni, Balazs; Debreceni, Laszlo (June 2014). "The Role of Homocysteine-Lowering B-Vitamins in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease". Cardiovascular Therapeutics. 32 (3): 130–138. doi:10.1111/1755-5922.12064. PMID 24571382.

- ^ Selhub, J. (July 1999). "Homocysteine Metabolism". Annual Review of Nutrition. 19 (1): 217–246. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217. ISSN 0199-9885. PMID 10448523.

- ^ Wald, D. S (2002-11-23). "Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: evidence on causality from a meta-analysis". BMJ. 325 (7374): 1202–1206. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1202. PMC135491. PMID 12446535.

- ^ Setola, E; Monti, Ld; Galluccio, E; Palloshi, A; Fragasso, G; Paroni, R; Magni, F; Sandoli, Ep; Lucotti, P; Costa, S; Fermo, I (2004-10-01). "Insulin resistance and endothelial function are improved after folate and vitamin B12 therapy in patients with metabolic syndrome: relationship between homocysteine levels and hyperinsulinemia". European Journal of Endocrinology. 151 (4): 483–489. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1510483. ISSN 0804-4643. PMID 15476449.

- ^ Guven, Aytekin; Inanc, Fatma; Kilinc, Metin; Ekerbicer, Hasan (2005-11-25). "Plasma homocysteine and lipoprotein (a) levels in Turkish patients with metabolic syndrome". Heart and Vessels. 20 (6): 290–295. doi:10.1007/s00380-004-0822-4. ISSN 0910-8327. PMID 16314912. S2CID 19304098.

- ^ Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration; et al. (2005-10-12). "Plasma Fibrinogen Level and the Risk of Major Cardiovascular Diseases and Nonvascular Mortality: An Individual Participant Meta-analysis". JAMA. 294 (14): 1799–809. doi:10.1001/jama.294.14.1799. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 16219884.

- ^ Welsh, Paul; Lowe, Gordon D.O.; Chalmers, John; Campbell, Duncan J.; Rumley, Ann; Neal, Bruce C.; MacMahon, Stephen W.; Woodward, Mark (August 2008). "Associations of Proinflammatory Cytokines With the Risk of Recurrent Stroke". Stroke. 39 (8): 2226–2230. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.504498. ISSN 0039-2499. PMID 18566306.

- ^ a b c Wiebe, N.; Field, C. J.; Tonelli, M. (November 2018). "A systematic review of the vitamin B12, folate and homocysteine triad across body mass index: Systematic review of B12 concentrations". Obesity Reviews. 19 (11): 1608–1618. doi:10.1111/obr.12724. PMID 30074676. S2CID 51908596.

- ^ Mahabir, S; Ettinger, S; Johnson, L; Baer, D J; Clevidence, B A; Hartman, T J; Taylor, P R (May 2008). "Measures of adiposity and body fat distribution in relation to serum folate levels in postmenopausal women in a feeding study". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 62 (5): 644–650. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602771. ISSN 0954-3007. PMC3236439. PMID 17457338.

- ^ Reitman, Alla; Friedrich, Ilana; Ben-Amotz, Ami; Levy, Yishai (August 2002). "Low plasma antioxidants and normal plasma B vitamins and homocysteine in patients with severe obesity". The Israel Medical Association Journal. 4 (8): 590–593. ISSN 1565-1088. PMID 12183861.

- ^ Zhu, Weihua; Huang, Xianmei; Li, Mengxia; Neubauer, Henning (May 2006). "Elevated plasma homocysteine in obese schoolchildren with early atherosclerosis". European Journal of Pediatrics. 165 (5): 326–331. doi:10.1007/s00431-005-0033-8. ISSN 0340-6199. PMID 16344991. S2CID 24549104.

- ^ Aasheim, Erlend T; Hofsø, Dag; Hjelmesæth, Jøran; Birkeland, Kåre I; Bøhmer, Thomas (2008-02-01). "Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (2): 362–369. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.2.362. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 18258626.

- ^ Damião, Charbel Pereira; Rodrigues, Amannda Oliveira; Pinheiro, Maria Fernanda Miguens Castellar; Cruz Filho, Rubens Antunes da; Cardoso, Gilberto Peres; Taboada, Giselle Fernandes; Lima, Giovanna Aparecida Balarini (2016-06-03). "Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in type 2 diabetic patients using metformin: a cross-sectional study". Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 134 (6): 473–479. doi:10.1590/1516-3180.2015.01382111. ISSN 1806-9460. PMID 28076635.

- ^ Akabwai, George Patrick; Kibirige, Davis; Mugenyi, Levi; Kaddu, Mark; Opio, Christopher; Lalitha, Rejani; Mutebi, Edrisa; Sajatovic, Martha (December 2015). "Vitamin B12 deficiency among adult diabetic patients in Uganda: relation to glycaemic control and haemoglobin concentration". Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 15 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s40200-016-0250-x. ISSN 2251-6581. PMC4962419. PMID 27468410.

- ^ Kaya, Cemil; Cengiz, Sevim Dinçer; Satıroğlu, Hakan (November 2009). "Obesity and insulin resistance associated with lower plasma vitamin B12 in PCOS". Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 19 (5): 721–726. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.06.005. PMID 20021721.

- ^ Iglesia, Iris; González-Gross, Marcela; Huybrechts, Inge; De Miguel-Etayo, Pilar; Molnar, Denes; Manios, Yannis; Widhalm, Kurt; Gottrand, Frédéric; Kafatos, Anthony; Marcos, Asensión; De la O Puerta, Alejandro (2017-06-05). "Associations between insulin resistance and three B-vitamins in European adolescents: the HELENA study". Nutrición Hospitalaria. 34 (3): 568–577. doi:10.20960/nh.559. ISSN 1699-5198. PMID 28627191.

- ^ Jayashri, Ramamoorthy; Venkatesan, Ulagamathesan; Rohan, Menon; Gokulakrishnan, Kuppan; Shanthi Rani, Coimbatore Subramanian; Deepa, Mohan; Anjana, Ranjit Mohan; Mohan, Viswanathan; Pradeepa, Rajendra (December 2018). "Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in South Indians with different grades of glucose tolerance". Acta Diabetologica. 55 (12): 1283–1293. doi:10.1007/s00592-018-1240-x. ISSN 0940-5429. PMID 30317438. S2CID 52977621.

- ^ Vayá, Amparo; Rivera, Leonor; Hernández-Mijares, Antonio; de la Fuente, Miguel; Solá, Eva; Romagnoli, Marco; Alis, R.; Laiz, Begoña (2012). "Homocysteine levels in morbidly obese patients. Its association with waist circumference and insulin resistance". Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation. 52 (1): 49–56. doi:10.3233/CH-2012-1544. PMID 22460264.

- ^ Reinstatler, L.; Qi, Y. P.; Williamson, R. S.; Garn, J. V.; Oakley, G. P. (2012-02-01). "Association of Biochemical B12 Deficiency With Metformin Therapy and Vitamin B12 Supplements: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2006". Diabetes Care. 35 (2): 327–333. doi:10.2337/dc11-1582. ISSN 0149-5992. PMC3263877. PMID 22179958.

- ^ Hampel, Howard; Abraham, Neena S.; El-Serag, Hashem B. (2005-08-02). "Meta-Analysis: Obesity and the Risk for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications". Annals of Internal Medicine. 143 (3): 199–211. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-3-200508020-00006. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 16061918. S2CID 15540274.

- ^ a b Rafnsson, Snorri B.; Saravanan, Ponnusamy; Bhopal, Raj S.; Yajnik, Chittaranjan S. (March 2011). "Is a low blood level of vitamin B12 a cardiovascular and diabetes risk factor? A systematic review of cohort studies". European Journal of Nutrition. 50 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1007/s00394-010-0119-6. ISSN 1436-6207. PMID 20585951. S2CID 28405065.

- ^ a b Jayedi, Ahmad; Zargar, Mahdieh Sadat (2019-09-08). "Intake of vitamin B6, folate, and vitamin B12 and risk of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 59 (16): 2697–2707. doi:10.1080/10408398.2018.1511967. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 30431328. S2CID 53430399.

- ^ Greene, Nicholas D.E.; Copp, Andrew J. (2014-07-08). "Neural Tube Defects". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 37 (1): 221–242. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170354. ISSN 0147-006X. PMC4486472. PMID 25032496.

- ^ a b Allen, Lindsay H.; Rosenberg, Irwin H.; Oakley, Godfrey P.; Omenn, Gilbert S. (March 2010). "Considering the Case for Vitamin B 12 Fortification of Flour". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 31 (1_suppl1): S36–S46. doi:10.1177/15648265100311S104. ISSN 0379-5721. PMID 20629351. S2CID 25738026.

- ^ Dawson, Earl; Evans, Douglas; Van Hook, James (1998). "Amniotic Fluid B 12 And Folate Levels Associated with Neural Tube Defects". American Journal of Perinatology. 15 (9): 511–514. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993975. ISSN 0735-1631. PMID 9890246.

- ^ Gardiki-Kouidou, P.; Seller, Mary J. (2008-06-28). "Amniotic fluid folate, vitamin B12 and transcobalamins in neural tube defects". Clinical Genetics. 33 (6): 441–448. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1988.tb03478.x. PMID 3048802. S2CID 5821824.

- ^ Metz, Jack (June 2008). "A High Prevalence of Biochemical Evidence of Vitamin B 12 or Folate Deficiency does not Translate into a Comparable Prevalence of Anemia". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 29 (2_suppl1): S74–S85. doi:10.1177/15648265080292S111. ISSN 0379-5721. PMID 18709883. S2CID 24852101.

- ^ Edelstein, T.; Stevens, K.; Baumslag, N.; Metz, J. (February 1968). "Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Supplementation During Pregnancy in a Population Subsisting on a Suboptimal Diet". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 75 (2): 133–137. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1968.tb02022.x. ISSN 1470-0328. PMID 5641006. S2CID 45266873.

- ^ Shahab-Ferdows, S., Randomized Placebo-controlled Vitamin B12 Supplementation Trial in Deficient Rural Mexican Women: Baseline Assessment, Transcobalamin Genotype and Response of Biochemical and Functional Markers to Supplementation. 2007: University of California, Davis.

- ^ Reid, E.D., et al., Hematological and biochemical responses of rural Mexican preschoolers to iron alone or iron plus micronutrients. Vol. 15. 2001. A731-A731.

- ^ a b c O'Leary, Fiona; Samman, Samir (2010-03-05). "Vitamin B12 in Health and Disease". Nutrients. 2 (3): 299–316. doi:10.3390/nu2030299. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC3257642. PMID 22254022.

- ^ Foran, Suriya; Wang, Jie Jin; Mitchell, Paul (January 2003). "Causes of visual impairment in two older population cross-sections: The Blue Mountains Eye Study". Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 10 (4): 215–225. doi:10.1076/opep.10.4.215.15906. ISSN 0928-6586. PMID 14628964. S2CID 29358674.

- ^ Pennington, Katie L.; DeAngelis, Margaret M. (December 2016). "Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors". Eye and Vision. 3 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/s40662-016-0063-5. ISSN 2326-0254. PMC5178091. PMID 28032115.

- ^ Al-Zamil, Waseem; Yassin, Sanaa (August 2017). "Recent developments in age-related macular degeneration: a review". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 12: 1313–1330. doi:10.2147/CIA.S143508. ISSN 1178-1998. PMC5573066. PMID 28860733.

- ^ a b Kamburoglu, Gunhal; Gumus, Koray; Kadayıfcılar, Sibel; Eldem, Bora (May 2006). "Plasma homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folate levels in age-related macular degeneration". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 244 (5): 565–569. doi:10.1007/s00417-005-0108-2. ISSN 0721-832X. PMID 16163497. S2CID 25236215.

- ^ Rochtchina, Elena; Wang, Jie Jin; Flood, Victoria M.; Mitchell, Paul (February 2007). "Elevated Serum Homocysteine, Low Serum Vitamin B12, Folate, and Age-related Macular Degeneration: The Blue Mountains Eye Study". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 143 (2): 344–346. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.08.032. PMID 17258528.

- ^ Christen, William G.; Glynn, Robert J.; Chew, Emily Y.; Albert, Christine M.; Manson, JoAnn E. (2009-02-23). "Folic Acid, Pyridoxine, and Cyanocobalamin Combination Treatment and Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Women: The Women's Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study". Archives of Internal Medicine. 169 (4): 335–341. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.574. ISSN 0003-9926. PMC2648137. PMID 19237716.

- ^ Heuberger, Roschelle A; Fisher, Alicia I; Jacques, Paul F; Klein, Ronald; Klein, Barbara EK; Palta, Mari; Mares-Perlman, Julie A (2002-10-01). "Relation of blood homocysteine and its nutritional determinants to age-related maculopathy in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (4): 897–902. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.4.897. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 12324306.

- ^ Morley, John E.; Vellas, Bruno; Abellan van Kan, G.; Anker, Stefan D.; Bauer, Juergen M.; Bernabei, Roberto; Cesari, Matteo; Chumlea, W.C.; Doehner, Wolfram; Evans, Jonathan; Fried, Linda P. (June 2013). "Frailty Consensus: A Call to Action". Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 14 (6): 392–397. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022. PMC4084863. PMID 23764209.

- ^ Vermeiren, Sofie; Vella-Azzopardi, Roberta; Beckwée, David; Habbig, Ann-Katrin; Scafoglieri, Aldo; Jansen, Bart; Bautmans, Ivan; Bautmans, Ivan; Verté, Dominque; Beyer, Ingo; Petrovic, Mirko (December 2016). "Frailty and the Prediction of Negative Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 17 (12): 1163.e1–1163.e17. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.010. PMID 27886869.

- ^ Soysal, Pinar; Stubbs, Brendon; Lucato, Paola; Luchini, Claudio; Solmi, Marco; Peluso, Roberto; Sergi, Giuseppe; Isik, Ahmet Turan; Manzato, Enzo; Maggi, Stefania; Maggio, Marcello (November 2016). "Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Ageing Research Reviews. 31: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.006. PMID 27592340. S2CID 460021.

- ^ O'Leary, F.; Flood, V. M.; Petocz, P.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Samman, Samir (June 2011). "B vitamin status, dietary intake and length of stay in a sample of elderly rehabilitation patients". The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 15 (6): 485–489. doi:10.1007/s12603-010-0330-4. ISSN 1279-7707. PMID 21623471. S2CID 23887493.

- ^ O'Leary F., F.V., Allman-Farinelli M., Petocz P., Samman S, Nutritional status, micronutrient levels and length of stay in an elderly rehabilitation unit. . Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009. 33(106).

- ^ Matteini, A. M.; Walston, J. D.; Fallin, M. D.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Kao, W. H. L.; Semba, R. D.; Allen, R. H.; Guralnik, J.; Fried, L. P.; Stabler, S. P. (May 2008). "Markers of B-vitamin deficiency and frailty in older women". The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 12 (5): 303–308. doi:10.1007/BF02982659. ISSN 1279-7707. PMC2739594. PMID 18443711.

- ^ Dokuzlar, Özge (2017). "Association between serum vitamin B12 levels and frailty in older adults" (PDF). Northern Clinics of Istanbul. 4 (1): 22–28. doi:10.14744/nci.2017.82787. PMC5530153. PMID 28752139.

- ^ a b Hunt, A.; Harrington, D.; Robinson, S. (2014-09-04). "Vitamin B12 deficiency". BMJ. 349 (sep04 1): g5226. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 25189324.

- ^ a b Quadros, Edward V. (January 2010). "Advances in the understanding of cobalamin assimilation and metabolism". British Journal of Haematology. 148 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07937.x. PMC2809139. PMID 19832808.

- ^ a b

- ^ Ralapanawa, Dissanayake Mudiyanselage Priyantha; Jayawickreme, Kushalee Poornima; Ekanayake, Ekanayake Mudiyanselage Madhushanka; Jayalath, Widana Arachchilage Thilak Ananda (December 2015). "B12 deficiency with neurological manifestations in the absence of anaemia". BMC Research Notes. 8 (1): 458. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1437-9. ISSN 1756-0500. PMC4575440. PMID 26385097.

- ^ Rosenberg, Irwin H. (June 2008). "Effects of Folate and Vitamin B 12 on Cognitive Function in Adults and the Elderly". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 29 (2_suppl1): S132–S142. doi:10.1177/15648265080292S118. ISSN 0379-5721. PMID 18709888. S2CID 1509549.

- ^ Smith, A David; Refsum, Helga (2009-02-01). "Vitamin B-12 and cognition in the elderly". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (2): 707S–711S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26947D. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 19116332.

- ^ Lewis, Monica S.; Miller, L. Stephen; Johnson, Mary Ann; Dolce, Evelyn B.; Allen, Robert H.; Stabler, Sally P. (2005-04-14). "Elevated Methylmalonic Acid Is Related to Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults Enrolled in an Elderly Nutrition Program". Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 24 (3): 47–65. doi:10.1300/J052v24n03_05. ISSN 0163-9366. PMID 15911524. S2CID 37997967.

- ^ McCully, Kilmer S (2007-11-01). "Homocysteine, vitamins, and vascular disease prevention". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 86 (5): 1563S–1568S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1563S. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 17991676.

- ^ Burton, Mj; Doree, Cj (2003-07-21), The Cochrane Collaboration (ed.), "Ear drops for the removal of ear wax", The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (3): CD004326, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004326, PMID 12918012, retrieved 2021-04-24

- ^ Vogiatzoglou, A.; Refsum, H.; Johnston, C.; Smith, S. M.; Bradley, K. M.; de Jager, C.; Budge, M. M.; Smith, A. D. (2008-09-09). "Vitamin B12 status and rate of brain volume loss in community-dwelling elderly". Neurology. 71 (11): 826–832. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000325581.26991.f2. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 18779510. S2CID 22192911.